We’ve been hearing a lot about health care integration lately, particularly around integration of behavioral health care with physical health care. (This term behavioral health can have several meanings; it is most often used to refer to “mental health plus substance use” disorders, which is how I am using it here.)

Since before Descartes, we have disintegrated man and woman into head and torso; brain and body; mind and soul. Only in the past hundred years have we begun the discussion about bringing these parts together again; reintegrating the psyche and the soma; integrating behavioral health and physical health.

The state of Maryland began this process last year, as its Department of Health and Mental Hygiene initiated discussions about merging the “Health” with the “Hygiene.” (As if cleanliness would make the difference.) For the past several months, stakeholders interested in the rights and well-being of people with mental health and addiction problems have been meeting, sometimes several times per week, with state and Medicaid officials, insurance representatives, advocacy organizations, and clinicians, to hash out what the new integrated Medicaid should look like. MCOs, ASOs, MBHOs, and ACOs are spit out like bullets, depending on your position about which organizational model is best able to balance enrollees' health with the applicable cost.

The Maryland Mental Health Coalition, an association of behavioral health providers and advocacy organizations, has been organizing an impressive effort, orchestrated by Linda Raines, who is also executive director of the Maryland chapter of Mental Health America (MHA), to unite our disparate voices into one. They are all mostly in agreement except for two main areas: splitting populations into more and less severe subgroups and the timing of integration of physical health into behavioral health.

Some believe that the populations of people with behavioral health problems should be split into those who are less severe and only receiving care from a primary care physician (PCP) and those who are more severely ill and receiving help from specialty mental health providers. The more ill ones, often with severe and chronic mental illness, consume the most resources, both in time and in money. But they are only 10-15% of the entire population of people with any behavioral health problem. The other 85-90% would receive a seemingly less integrated form of care, called collaborative care, which recognizes the fact that the supply of mental health providers is not enough to meet the demand for the entire population.

Collaborative care, which has had somewhat positive to mixed results with respect to outcomes, uses psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and other mental health providers to review a patient’s electronic health record and discuss the patient’s problems and needs in a collaborative format that provides clinical decision support to the primary care clinician who is primarily managing the care. This is often telephonic and web-based support, though some provide support that is co-located with the PCPs.

The other part of the discussion is the degree to which the behavioral health care should be carved out versus provided by the parent managed care organization. The American Psychiatric Association has a position statement opposing the concept of carve-outs. The paper suggests that:

“Mental health and substance abuse integration occurs when benefits and services for people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders are integrated, funded and administered no differently than for those people with other medical/surgical illnesses.”

The Maryland Psychiatric Society is also pushing on this point, suggesting that “financial rewards and penalties for the payor(s) should be integrated in such a manner that they are incentivized to coordinate services and prevent negative outcomes regardless of who is paying the bill. ” The Maryland chapter of MHA and most of the Coalition members feel that an Administrative Services Organization (ASO) model that uses a behavioral health home for people with severe illnesses, and a collaborative care model for the other 85%, will be the best balance. I liken this to how people like their band-aids torn off – with a sudden amount of pain that subsides quickly, or a drawn-out but consistent level of pain for a longer period of time. It’s a personal choice.

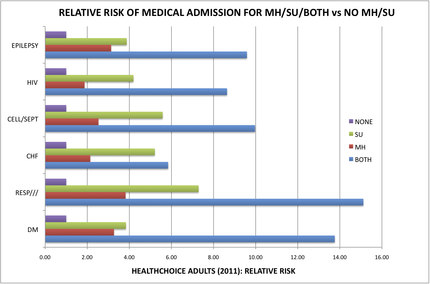

Ask the people who have both a medical problem as well as a behavioral health problem. People with both mental health and addiction illnesses in Maryland Medicaid are 8-15 times more likely to be medically hospitalized for problems like diabetes, epilepsy, infections, and heart failure, than those who do not have a behavioral health condition [See chart below]. Wow! That disparity is impressive.